Imagine the Kim Novak character from Vertigo.

She comes through the movie screen with all her drifting blonde ways and is pursued by a cinema professor teaching a course on Hitchcock. She is haunted, confused, has no idea of the dark side of her personality. And all the while, she is being stalked by Psycho’s Norman Bates, who has fallen through the same movie screen.

This is the seed for the MOVIELAND QUARTET, a four-novel series inspired by the films of Alfred Hitchcock, particularly Vertigo, Psycho, and The Birds.

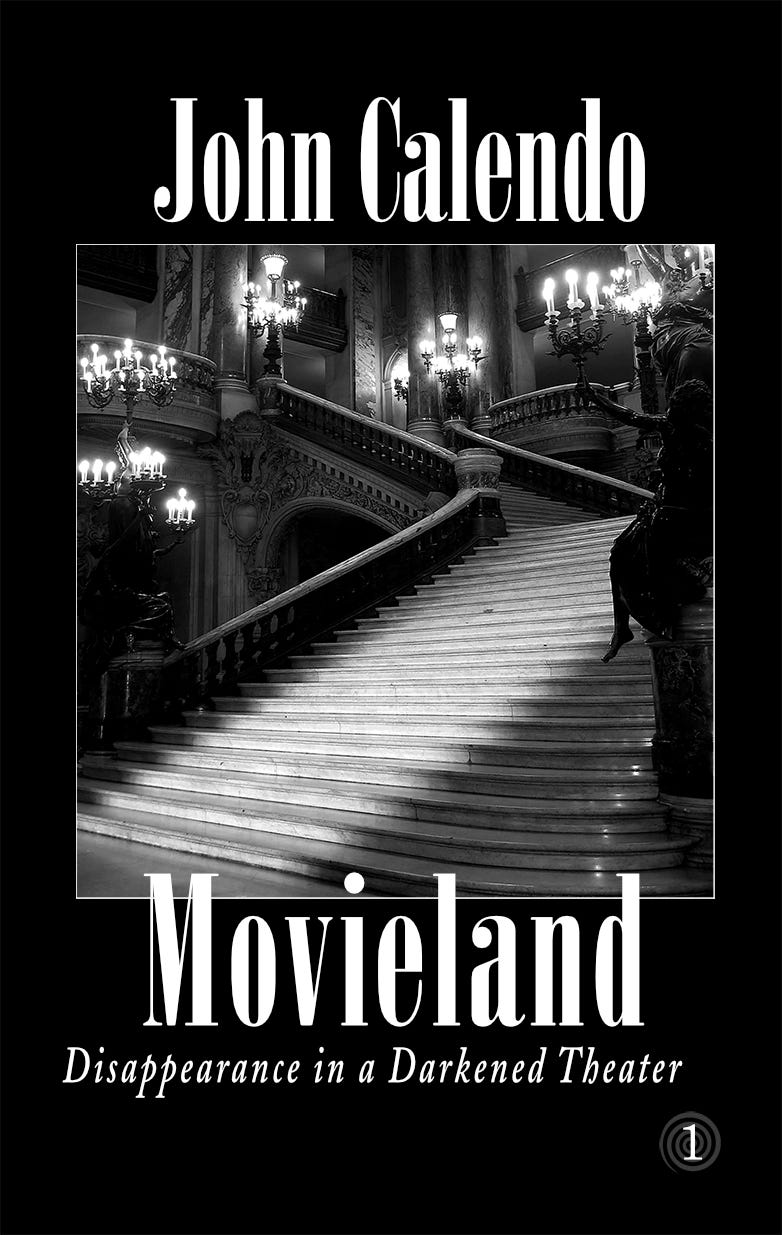

The Palatine Theater

1

Six Forty-Three AM

Never begin with the weather. You’re clearing your throat when you begin with the weather. Best to begin on the run. A chase, a murder, a cryptic remark. All that is to come. We begin with the weather.

And the time.

It’s drizzling on Venice Beach. Good; you’re seeing the theater in its element. A fine mist-like rain sweeps up Pineapple Street, where the Palatine Theater stands at the top of the hill, brooding over the beach, a movie palace once, built in the style of a square Roman temple.

Its façade of battered nymphs, along the sides of the building, darken with moisture. They’ve long been neglected on that upper-story ledge, holding up cracked garlands or standing seriously with water jars on their shoulders.

At each corner towers a mysterious guardian, a Vestal Virgin, her face blurred by stony gossamer veiling, which clings to the features as if the rain had seeped into the limestone. The Vestal of the North, The Vestal of the East, the Vestal of the South, and facing us, through her stone veil, the Vestal of the West. Their hands cup small stone flames, and each one stands on a square platform with an incised legend that announces the point of the compass she governs.

They are austere matrons of a patrician race, these Keepers of the Flame, and they are all that remain to watch over this destitute palace of ancient, abandoned cinema. Their backs are turned forbiddingly to the line of gay girls that raise the looping garland. The girls themselves are divided into two trains. At their center stands a serious maiden holding up a water jar on her shoulder, separate and singular, a train of maidens to either side of her, the balance of artless Grecian girls holding up the acanthus leaves resemble something you’d see on a Wedgwood cup…if that cup were smashed. For this limestone population has been hurt by time, dissembled by weather. The missing noses, the broken lips, the lost hands—it’s as if a war had flared up among the nymphs, and each one, in her way, lost.

The birds too have done their worst, and in this fine mist, you might imagine not birds but tears have left stubborn white stains on faces and togas.

Among the Venice Beach locals, among those who grew up beneath the tread of this Attic dance, the nymphs are called ‘The Weeping Maidens.’

It is morning — well, not quite morning. If the sun has broken the horizon, it is muzzled behind a wool sky. Everything is of an even grayness. The only sound, the sigh of the sea. The Pacific rolling sluggishly, turning in its sleep.

Fix this image in your mind now: the theater in the rain, under uncertain skies, under uncertain light. You have come upon the Palatine Theater when it is most itself. Full of that long brooding that all ruined things have. Haunted by what it once was, so gay, so young, silent movie stars arriving under the marquee in their satin wrappers and flour-white makeup, waving to the Movietone cameras, to the fans clustered behind barricades, swanning up to the clunky microphone to speak with the effusive, chattering radio host — a hundred glittering nights of a hundred glittering premiers.

The Palatine was, in keeping with the style of the ‘20s, built like a stage theater. With stage shows planned between the movie features. It had box seats and all the gilt trappings of a night at the opera, but in the end, it was only on premiere night that the screen would descend into the floor and live shows be put on, and by the stars themselves, for each other primarily, gently chiding the industry with inside jokes.

Backstage, out of sight, was a jungle of ropes, pulleys, trapdoors, rigs. Ancient scenery, painted backdrops on flies, and a flying Pegasus that once winged a swashbuckling Douglas Fairbanks onto the stage for the premiere of The Thief of Bagdad. Devilishly handsome, he hopped off the contraption as deftly as a dancer, a fine athletic specimen, bare-chested in leather britches, with a scarf wrapped around his head as colorful as an Amazonian parrot, and piratical mascara outlining the eyes. He made a theatrical flourish of his hands and took a low bow, setting off a wave of girlish squeals to the highest reaches of the theater.

The Palatine was a gem. It was a Greco-Roman palace in faraway Venice Beach that the studios felt lent their showcase productions a certain prestige, the trek in a parade of flashy motorcars to the theater’s out-of-the-way location adding to the effect. It did not matter that Venice Beach, after so much hoopla, after its canals and real-estate hype to become ‘the Lido on the Pacific,’ had debuted instantly as a honky-tonk district for sailors and Ferris wheels. The tawdriness made the Palatine Theater all the more striking atop its hill on Pineapple Street, a fabulous pearl set against threadbare black velvet. The Palatine was itself a kind of star, demanding, temperamental. You had to come to it; it did not make allowances for you.

But time is not kind to stars.

They slip out of favor.

They slip, sometimes, out of orbit.

Things happened. Peculiar things. Death came to the Late Show. The Palatine’s founder, a visionary, was killed by ‘something in the dark’—so his widow claimed and still maintains. Actually, he limped home to die in his bed, carried there by two bewildered teenage ushers who found him sprawled behind the screen, babbling, delirious. A funeral of sorts was held in the theater, which became a swamp of flowers, down the aisles, overflowing the stage, the heavy perfume so cloying that fire doors had to be opened.

But few attended. The flowers were all that remained of those who remembered the charismatic British occultist who built the theater, the flock who thought they owed their careers to him: his followers, the beens, has-beens, and never-weres.

Once Arthur Aubrey was in the ground (of the Hollywood Cemetery, appropriately), his widow left the theater to its own devices — other managers, hired help. And with neglect came a sort of devolution. The Palatine turned.

Darkened.

The marble of its grand staircase now seemed to take on a green, sickly sheen. Around certain corners on your way up the staircase to the balcony, you might catch a sudden fusty drift, a dusty funereal scent of flowers that had somehow seeped into the fabric of the carpet, as if its raised vermillion roses were breathing forth decay.

Maintenance fell off. The theater had to be closed. Staff was dismissed, including a stalwart in his sixties, built like a jockey, who could still fit into his bellboy-styled usher’s uniform, putting away the white gloves and snappy bellboy cap in an elegiac locker room ceremony that signaled the end of an era to the others. Months went by, and the theater stood unlit at night, an embalmed presence at the top of Pineapple Street. Then without fanfare, on a random Thursday, the plate glass doors reopened, against the wishes of the widow, on the insistence of the boyfriend, Aubrey’s most devout follower. But again there were problems, neglect, closures. A sloppy nostalgia piece ran in the Los Angeles Times about old Hollywood, with the farewell ceremony of the Palatine ushers as its symbolic centerpiece. The publicity was a comeback of sorts for the theater, comebacks being the mark of a true star.

Soon a new scheme arose.

When the theater was last opened to the public, the marquee bled. Large triple Xs in red plastic towered over the beach like scars, demeaning the grave Vestals who continued to hold court above the jutting marquee. Double-entendre titles, all winks and elbow jabs, whose very proximity seemed to transform the carefree nymphs into bold sisters flouncing about in diaphanous lingerie.

The great Palatine had become a porn house. Sticky floors, ripped upholstery, missing seats. Furtive acts in corners, men with men, a random woman working the aisles, the darkness being kinder to her lipsticked trade, a restless audience echoing the mechanical scenes above them, in the wintery light that slanted off the screen onto the gap-toothed rows. Shadow denizens amid imperial ruin.

Such as it was, this was the last puff of magic at the Palatine Theater. Before the talk of bulldozers. The strategy of controlled demolitions.

But there was one guardian Vestal left, not made of stone. Miriam Thorncraft, daughter of the great director Edward Thorncraft, who, against the protests of the widow, pulled strings to declare the theater at the top of the hill — long a striking fixture on the flat Venice skyline — a landmark, donated the landmark to UCLA and vowed to raise money for its restoration. And so the wrecking ball was stopped in mid-swing, and the widow, in her gentle alcoholic haze, was at odds with her good friend Miriam, who should have had more sense. Who knew very well what this theater really was.

Alone at night, with a drink clinking in her hand, the widow would ruminate:

A landmark! … the word was like a door slamming. Now they would never be rid of it. Do-gooder Miriam! Getting the Chamber of Commerce involved, using her famous name, charity this and thats for the Preservation of the Palatine. Was she mad!

And so the widow’s nights would rage on in a slurred blur for she knew, as did Miriam, that there was a curious architectural folly on the roof of the theater. Well, that’s what people thought it was, people who shaded their eyes against the beach sun and happened to glance up: a Roman rotunda in a circle of marble columns, under a pretty white dome. Something you might find on an English estate, to set off the green lawns with a bit of the ancient. To those of a more prosaic bent, it recalled the top of a wedding cake, an unexpectedly stately crown to complement the dancing nymphs garlanded below it.

But to those who knew— the widow, certainly Miriam — this folly was no folly at all. It was, in fact, a temple. And in true occult fashion, it was hiding in plain sight. One might say the temple was the sole reason this particular movie theater was built. The reason why so much of its history was never rational to begin with, for the Palatine was no stranger to the strange.

Somewhere in its slumbering depths were the ghost traces of a December night in 1964. A beauty contest on stage and a young woman, whom the tabloids would call ‘a starlet’ and more sensationally ‘the Wayward Redhead.’ She was a shapely girl come to Hollywood with dreams that had lately taken a beating, a girl prone to little indiscretions. Though few remember her now, an urban legend, for a time, sprang up around her. It was said that she became lost in the theater. In her confusion to find her way, she turned a wrong corner in the dark and then — as Hollywood Exposé memorably put it — ‘she simply walked right out of this world.’

PREVIEW: On a December night in 1964, a young woman gets lost in the dark of the Palatine Theater. In the next chapter, we meet the great director Edward Thorncraft, whom many readers will recognize by a different name.

I will be looking forward to Wednesdays now!

The music of your words thrills me! Thank you.