Believe.

34

Thunder and Lightning

He was wandering somewhere, searching for something, when he was shaken. He opened his eyes.

“Tom, I’m so —“ But the sky lit up behind her, and her low, sultry voice was drowned out by a crack of thunder, tumbling and rumbling down the sky. He was coming awake now.

“Here,” he said, still a bit dreamy, scooting over on the futon. And before he knew it, she had joined him under the covers, shivering a bit. “I’m such a child about thunderstorms. It’s embarrassing. Oh, Tom, just … just hold me.”

He had waited for this moment, waited guiltily, wondering if it would ever arrive. And now she had come to him as if through the lightning itself, with the sky flashing behind her outside the windows. Looking fragile in his man-sized pajamas from Paris.

“I thought I was in the cave again. I was cold, frightened. I was going to be in the dark forever!”

“It was a dream.”

“Was it? … Was it always a dream?” she asked despondently. “Did I even fall in the Bay at all?”

“You didn’t fall, Eden. You persuaded yourself that you fell. Actually, you jumped.”

“No! I wouldn’t … I …” her voice crumbled. “… couldn’t.” Slowly, with a sort of dazed realization: “Did I? Did I really?”

He grimaced sympathetically.

Her hand went to her neck, lingering on her clavicle. “Why would I do a thing like that? Why don’t I remember these things? My mind is all jumbled up!”

It distressed Tom to see her so ill at ease, but he cautioned himself to say nothing. How could he tell her she was written to be confused and haunted?

“When I shut my eyes, Tom,” her voice came low and husky, “I sometimes see a woman, very proud, very haughty, standing on a stair, looking down at me.”

“The woman in the portrait,” Tom confirmed

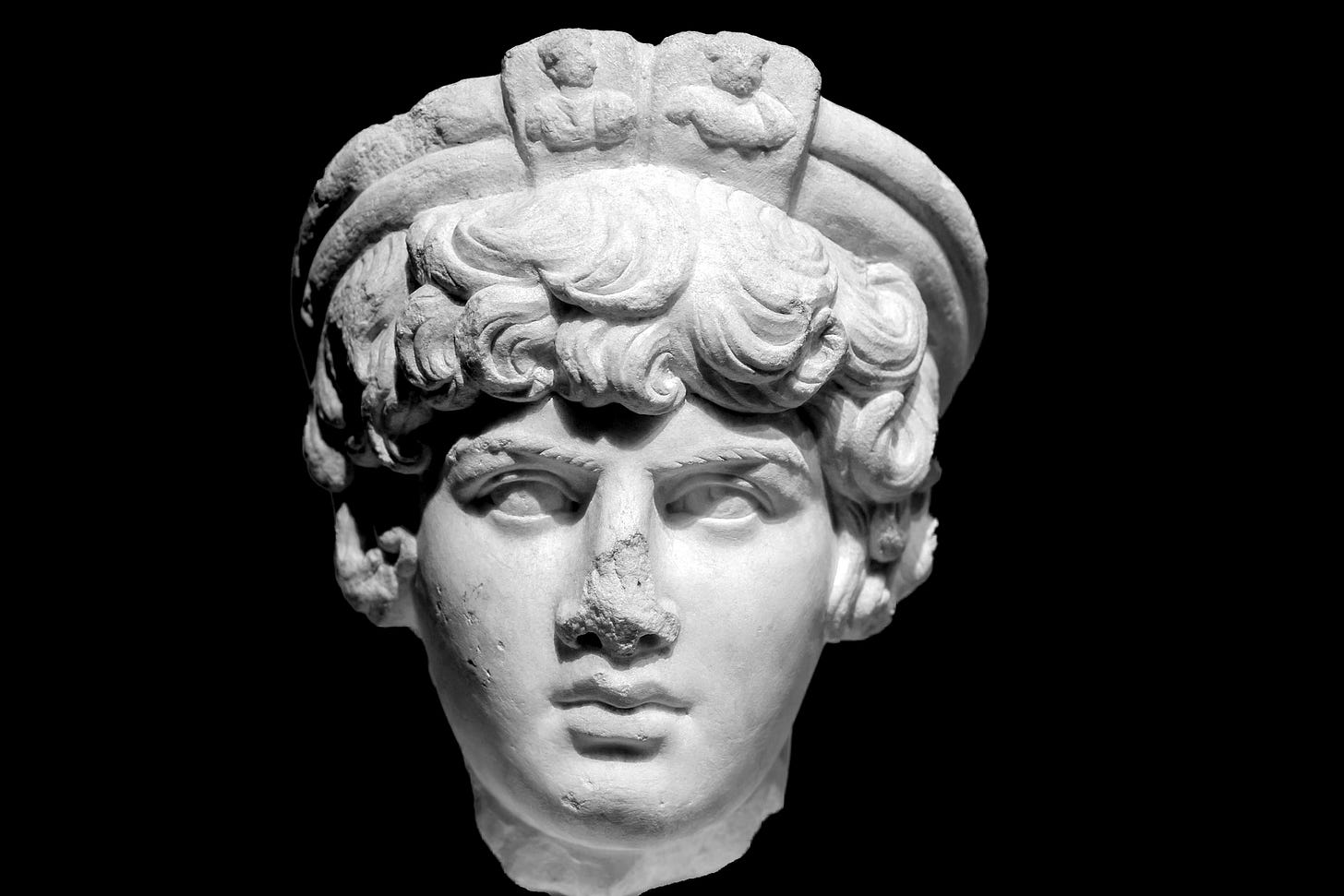

“Yes, that’s it! I’m sitting beneath a painting! She wears a diadem — my eyes always go to it. It’s lovely. A half-moon of diamonds in her hair. How rich and regal she looks in her creamy white ballgown with a bustle, from the turn of the century … the bodice low, the shoulders so white and exposed. But the way she looks down at me, with such disdain, as if she’s looking through me. She … she wants to control me!”

“It’s make-believe, Eden.” It was, in fact, a plot device in Fog, but he stopped himself from bringing up a subject that he knew would disturb her.

“Something happened to this woman,” she continued searchingly. “Long ago. Something terrible! She! … she jumped too! From a high … Oh, Tom, that terrible thing that came for her is coming for me!”

She gasped suddenly, her eyes wide with realization, a fleeting image from her other life, and for a moment the room fell silent, weighing heavily, waiting on her next words. They came breathlessly, whispered, in a sort of terrified wonder:

“Driving … me into madness!”

“Eden, look at me.”

The serenely beautiful face met his eyes.

“Do you trust me?”

She nodded dutifully.

“Do you hear that thunder? It’s rolling in from Long Beach. Soon it will be breaking overhead. That’s real. This room. This room in Westwood. My desk, which used to be messy but you straighten up every day, my desk with the coffee rings that won’t rub out, this room with the Venetian blinds drawn up high on that silly lopsided angle: all real. The woman in the painting, not real. She has no power to command you. No power to possess you. You have your own power here, your own mind here. You have free will!”

“But, Tom, I want so badly to be there with her! I long to sit in front of that portrait. Can’t you — won’t you — put me back?”

“How would I do that, Eden?” This was the closest she had come to phrasing it. He must be careful now. It must come from her.

“I was just hoping — maybe, it’s foolish — but I was hoping you had figured it out. You know so many things. Impossible things. Things about me you couldn’t know, shouldn’t know. It is your theater. You work there. You must know how.”

“The Palatine Theater is a mystery to me too, Eden. And where would I put you, even if I could? The cave? The Nowhere Place?” He was purposely using loaded words that would discourage this dangerous line of questioning. “With the terrible ball of light?”

“N-no … not that! Never again that. I guess … I hoped … you might just take me home, Tom.”

There was now an unreal moment of silence. Even the rain seemed to stop tapping on the window pane.

Taking a deep breath, she said what had been hanging in the air since the beginning.

“Back into my world,” she said, embarrassed. “Back into my …” She hesitated before saying the word, and when she said it, it was with a grimace, as if she were handling the word with tongs. “… film. The one you call Fog”

There it was, finally. The last stage: Acceptance.

There are five stages of grief, and the first is Denial.

It had begun on the evening of Jewel Thief by Night. He sat beside her on the couch, but his mind was not on the hero slinking along the midnight rooftops of Monte Carlo. Tom was overlaying the images with his own dilemma, feeling that he too was leaping from one high hotel balcony to another as he calculated a future life with Eden. Among many aerial tricks, he must avoid ever mentioning Fog.

This would be hard for the scholar. Eden was in blind denial of what they both saw when the screen swirled open, when the back of the theater was filled with whirling gold light. By the time the Jewel Thief fireworks blazed up on the TV screen, Tom had decided Eden’s denial, in all its extremity, must be encouraged, even pampered. Questioning something as essential as one’s own realness would not end well. No one can stare into the sun, or a paradox, for long.

But it was not to be.

Eden’s mind was alive with spontaneous free thoughts now, and the denial Tom counted on proved brittle, breaking quickly into five separate pieces.

The second stage of grief, Tom was to witness, is Anger.

When they went to the police station, they were shown to a back office that was a warren of cubicles, staffed, it seemed, mostly by female officers in blue uniforms, their hair in utilitarian buns, their attitude no-nonsense, when not exactly grim. They were women holding their own in a male preserve where the noisy, overheard talk could be as salty as that in a men’s locker room.

Eden and Tom sat before Officer Lin, an alert Asian woman with photos of two small children pinned to a corkboard panel. She clicked away at the keyboard. No, she told them, there were no flags for an Eden Windess. No one had filed a missing person’s report. Then, for the sake of completeness, she asked the obvious question: had they tried calling Mr. Windess? Tom explained that his companion had recently suffered a fall and couldn’t recall many basic things about her past, including phone numbers.

The woman clicked away and studied the screen. “No listings for a Windess in the San Francisco White Pages,” she said. “Is it a private number?”

Eden was perplexed for a moment. “I know! Try Arcadia-Pacific Airlines.”

Tom was amazed she remember that detail. The real Eden Windess, along with her brother, had inherited their father’s airline company. Her husband had married into the business, which, as Fog showed, he now exclusively ran.

“No listing for Arcadia-Pacific Airlines. Are you sure it’s located in the Bay Area? Let me do a wider search.” More clicking keys, then a frown. “No, no such airline anywhere. You mentioned a brother. Same last name?”

“It wouldn’t be, would it?” reasoned Eden softly. “Windess is my married name.” She gave Tom an embarrassed look. “What is my brother’s name, Tom?”

Of course, Eden wouldn’t know. She was never called by her maiden name in the film. “Dwayne—” he began.

“That’s it!” cried Eden eagerly. “Dwayne Carlyle. That’s the name! It just came to me, like a puzzle piece snapping into place: I was a Carlyle before I was a Windess.”

Officer Lin watched the couple with the deadpan composure of someone who deals with difficult people all day every day. “Spelling,” she asked flatly. Tom accommodated, and she clicked out the name on her keyboard. “I’m coming up with four Carlyles in the Bay Area. A Rita, an Anita, a Valdez, and a Carlotta. No Dwaynes.”

During the tense ride home, Eden brooded angrily “Why isn’t my husband looking for me! And what happened to the airline? Our money depends on that airline! It can’t have just disappeared. And where’s my brother! My fool playboy of a brother! He wouldn’t stay quiet. He lives on a stipend, a tiny fortune. He’d be complaining to all the newspapers! Tom this is terrible. It’s … it’s as if they’ve all been wiped off the face of the earth!”

And again, Tom disciplined himself to say nothing.

For the next few days, he tried to assuage the discontented Eden. One interesting side effect, she was forcing herself to remember odd bits of the film, or the part of the film that had played out on screen during the first 43 minutes, before she leaped into the murky waters of the bay. Of what happens afterward, she seemed completely unaware, as unprepared as the audience for the unmasking that would rock the film’s finale.

The memories frightened her. They came in flashes, fragments, sudden shifts in perspective. Her streak of righteous anger, the entitled sense of being wronged and neglected, were quickly eclipsed, under the planetary shadow of this other world coming too close upon her, this half-hidden life she had lived. And by week’s end, her discontent fell apart into something more desperate, a state of knowing and not knowing. Eden had entered the third stage of grief: Bargaining.

She now took to tidying up his apartment when he was in class. In restaurants, she’d have the waiter pack up the food she couldn’t finish (which was most of it), and then during the walk home along the marina search out some sleeping beach beggar and quietly place the bag by his side. It was as if she were trying to forge a deal with the universe — this universe. Humble altruistic ‘good works’ that might confer a realness upon her that she had lately come to doubt.

One day, not long after, she showed him something she had found pressed between the heavy pages of a massive Encyclopedia of Film that he kept, more out of sentiment than anything else (it was a gift from his thesis advisor), on display on a pedestal in his office, opened randomly to one or another of its entry-rich pages.

“What is this,” she asked, handing him a folded piece of construction paper that had slid out of the book when she moved it to dust.

“It’s a birthday card from my daughter,” he said, smiling down at the crayon handiwork. “Joyeux anniversaire, Papa!” it said in many colors beside a stick figure of a little girl with corkscrews for hair.

“What language is that? It’s so pretty. Wait, I — is it French?”

“Yes, Eden, it is.” He opened the card and felt a lump form in his throat.

“You look so sad, Tom. What does it say?”

“Je t'aime’” he replied, a bit strained. “It means, I love you.”

Below the inscription was a name, “Jean Day,” printed out in neat crayon letters, next to a small, square snapshot of a pretty curly-haired child in a ballerina pose that had been decorated with glitter and paste-on hearts.

“She was such a sweet little girl,” he said wistfully.

Eden was confused. “But I know French, “ she murmured breathily. “I should be able to read that!”

Still lost in reverie, Tom spoke without thinking. ‘You only think you know French. Eden Windess knows French. It’s part of her backstory. A skill never displayed in the film but part of the classic, upper-class education for girls of her social set.” He realized too late he had drifted into professor talk and wedged open a pandora’s box he must never open, the suggestion that she might be acting a part.

Her shoulders slumped. “Nothing makes sense anymore. I … I don’t make sense anymore.”

And so they had come to the penultimate stage of grief: Depression.

The darkness before the dawn.

It didn’t feel like a victory.

Her film, she said. The one he called Fog.

It had been a week of mood swings, and now she had come to the end. Acceptance, the final stage, the stage that was supposed to demolish the grief. Eden seemed more downcast than ever.

He kissed her brow as she lay beside him, and she rested her head on his shoulder like a troubled child.

“I have an idea,” he said, “would you like to see San Francisco? We could go there for a weekend.”

“Could we!” She turned to him excitedly. “That would be wonderful!”

“It will be a very different San Francisco, you understand, a San Francisco of this world. A lot has changed since 1959.”

She was confused.

“1959 is the year Fog came out,” he explained. “Do you know what year it is now?”

She grimaced, preparing herself for yet another shock in this new world

“This is going to sound like science fiction to you, but it’s 2010.”

She sighed ruefully. “Of course, it is,” she said flatly. “Everything is crazy here. Why not 3010! 7010!”

Tom smiled. “Sarcasm, Eden? You are coming along. Anyway, you must have realized it already. The cars, the hairdos—”

“The blue jeans!” she cried. “I was meaning to ask you about that. What happened to men in fedoras and women in beautiful furs? When did everyone become farmers! And the long hair! When did men become nature boys! I tried to tell myself, this is Los Angeles. ‘LaLaLand,’ ‘Fruits and Nuts’ — that sort of thing.”

“And what about all of our ‘flashing gadgets,’” he prompted merrily. “Isn’t that what you called them at the mall?”

“Well, I always heard Los Angeles was fast.”

“Eden, you’ve come 50 years forward. It must feel like the future to you, but that isn’t quite true, is it. It isn’t true because for you the past is the future. From our perspective, your life is a movie, a reel of film, and time for you is just a sort of arrested present, sealed into the frames of that film. It can only go round and round. Your sense of a future is simply a repeat of the past. There might be a comfort in that, but that’s not how time really works. There’s a finality to time here. There’s no return, no going back. Time only goes forward … into the unknown.”

Her smooth brow furrowed. “Please Tom, you’re giving me a headache.”

But he couldn’t help himself. “Something fantastic has happened to us, Eden. Do you see that? Somehow you’ve broken out of the loop. It might have felt like you were drowning, but somehow you’ve fallen through the film into … into reality! How? I can’t even guess. What happened at the Palatine Theater is beyond my abilities.”

“Oh, Tom,” she said with new distress.

“I’m trying to understand it. Tomorrow I’m going to see a woman, the widow of the man who built the theater. She may know what’s at the bottom of this.”

“You mean” —her eyes grew large — “maybe there is a way to bring me home?”

He caressed her face. “We’ll see.” Those words were the formula he used with his baby daughter when he meant no but didn’t want to upset her. Tom had no intention of letting Eden go.

He changed the subject. “You still want to come with me, I hope. To my … to our … San Francisco.”

“Oh yes, yes! The air there, the food, the people … I think it might all be better. But don’t you have to work?”

“I have class on Tuesdays and Thursdays. But we can fly out on a Friday morning and come back late Monday night. A nice long weekend.”

“Yes, please!”

“And we’ll be total tourists, corny as heck! Trolley cars. Chinatown. Just you and me.”

“And Ernie’s!” cried Eden happily, for an image had come to her: a famous steakhouse, with red-flocked wallpaper and glowing oil lamps, that provided the backdrop for a romantic interlude in Fog.

He lowered his voice consolingly. “Eden. I’m so sorry. Ernie’s doesn’t exist anymore. It’s now a—”

“Don’t tell me,” she pleaded, shutting her eyes.

He took her chin in his hand. “We’ll find our own place, okay? Make our own memories.”

She smiled weakly.

Just then there was a double shock of lightning. Eden gripped him as a calamitous outbreak of thunder rumbled down the sky. She looked up into his eyes. The moment had come. He kissed her, kissed her passionately, and, against the shattering flashes of light, the night of thunder and lightning turned into a night of much, much more.

Movieland continues in Book 2: Occult Hollywood.