The signs.

18

Hidden in Plain Sight

A grim thought crossed Tom’s mind: he might be looking for a body.

Under the wintry house lights, the balcony was a wreck. Slashed upholstery, missing seats, stained carpet. A section of a row — three connected seats — had broken free and tumbled midway down an aisle where it lay on its face. By the entrance, a fallen plaster column had smashed into several large white chunks that Tom had to sidestep. Teal blue fragments, large and shaped like puzzle pieces, had come loose from the ceiling, a ceiling, Tom saw, which sported crackled sketches of an astrological sky.

So this was why the balcony was kept hidden behind off-limit signs. It was ugly. Ugly and dangerous. Scarred from a time when the Palatine was neglected. The barbarians had invaded, lured by the triple “X”s on the marquee. Toga-ed figures, no longer gods or goddesses, had been knocked off wall niches and lay in disembodied carnage along the side corridors. The horseshoe shape of the balcony, meant to evoke the circular Council of the Gods, had become an Olympus in ruins, turned by a brutish horde into white rubble.

From where Tom stood, the horseshoe balcony looked like two arms about to embrace the screen. He went down an aisle, searching the rows, under the seats. Everywhere plaster sky had rained down in teal-blue chips. Ripped-up holes showed in the carpeting where a shoe might snag, balance be lost. What violent surprises had awaited his swaggering student prowling around here in the dark?

When he reached the bottom row, he crossed to his left to search the hallway behind the opera boxes. The narrow passage was empty. For good measure, he tried all the doors, rattling them loudly. The doors were securely locked. So far so good. He made his way again across the bottom row to the other half of the balcony.

Here, on the right side, someone had made an effort to sweep the destruction to the wall. Still, the way was not clear of debris, the wall itself shallowly embossed with a line of maidens, peacocks trailing feathers, leaping stags. He followed the pastoral molding into the hallway behind the opera boxes, trying each of the locked doors as he had on the opposite side. It was only when he reached the end of the hall — or so an illusion in the architecture made it seem like the end — that he made out a corner where no corner should be. He turned into it and found himself in a dark room that, after he clicked on his cell phone, revealed itself to be L-shaped.

A door in the wall had been left ajar.

Tom entered. Entered into dark space. By the feeble light of his cell phone, he found a Pompeian side table by the wall with two black vases on it. The vases were ornamented with orange youths at naked play, their profiles Roman, their cap of hair in tight curls. In one vase were long yellow tapers; in the other, long wooden matches. Tom lit one of the tapers, and the shadowy room came alive.

Tom now saw he was in an antechamber, very much in keeping with the Palatine’s Roman theme. Wide steps led up to a portico supported by Corinthian columns. In the center of the portico was a bronze door, worked with various mythological beasts on the metal plate. Above the portico, on a jutting ledge, was a triangular pediment that extended from wall to wall. On the pediment were incised letters, each word separated by a middle dot.

Tom barely remembered his Latin from long-ago high school classes — a requirement once of a classical prep-school education — but he recognized "Pontifex Maximus" to mean high priest, or rather, the highest priest. "Fecit" was an easy verb: it meant "made." The first two words, now that he looked at them, were a name. You needed only to transpose the "v"s with "u"s to realize whose it was: “Arturus Aubrey High Priest Made This.” Arthur Aubrey, the Palatine's occultist founder.

With taper in hand, Tom climbed the four shallow steps and found the heavy bronze door slightly ajar. It was wide enough to pass through, and he slipped in, candle first.

He was now in a dark, narrow stairwell that led up to another bronze door, catching coppery highlights from the flickering taper as he approached. The door, he saw, had a small triangular pediment over the doorframe. He lifted his candle to read it:

“Here Dwell the Immortals.”

This door too had been left ajar, and so he again slipped through, candle first.

What he found inside took his breath away. He was standing in a miniature of the Pantheon in Rome, under a vast vault with light streaming down through an open oculus that was centered at the apex of the dome. The light, he knew, was meant to travel around the circumference of the temple counting off the daylight hours, but at the moment, it was noon, and the light shone straight down in a bright circle, illuminating a marble altar.

Unlike the dome’s original in the Circus Flaminius, which Tom had visited, camera in hand, when he was teaching at the Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia, the oculus had a glass covering to keep the rain out. Otherwise, everything seemed convincingly duplicated, if a fraction in size, including the plaster coffers that scaled the sides of the vault in little indented squares.

What Tom had always thought was a whimsical folly of the Palatine’s design — a domed Greco-Roman rotunda on the roof of the theater — seemed now quite seriously a temple.

Had Pauline been looking where she was going, she would not have passed her yellow Jeep by the side of a Venice canal, crossed over a bridge to the wrong end, gone further astray into quiet residential streets, still ruminating over Dante, before finally making the wrong turn that would prove so fortuitous.

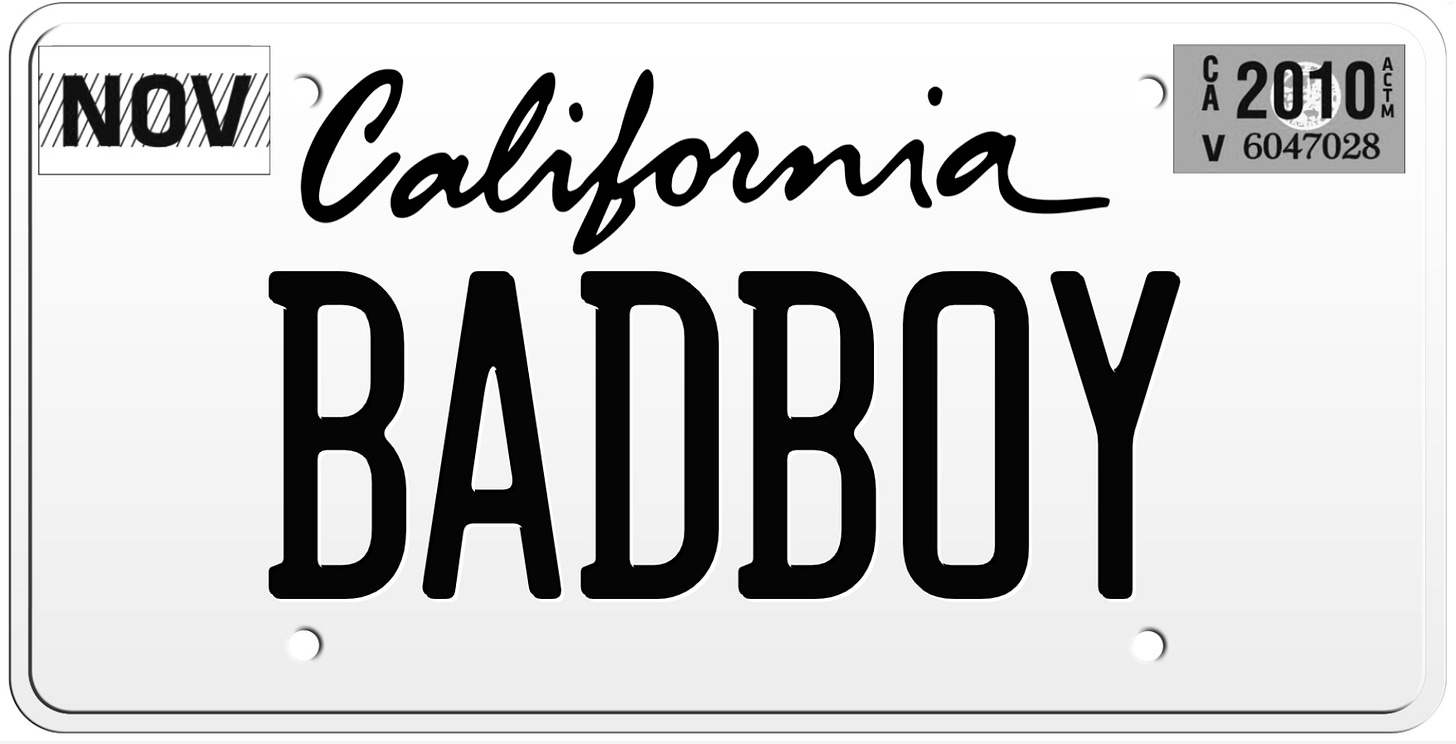

There under a tree, under a shower of lavender blossoms, was Dante’s silver Porsche, the sporty Boxster he was so proud of. She recognized it even before double-checking the vanity plates. Of course, the plates said

The name of Dante’s production company.

At the moment the sports car looked like a float in the Rose Bowl Parade. Jacaranda blossoms carpeted the roof and hood, concealing the windshield under a bell-shaped curve of fragrant lavender petals.

Pauline reared up sharply, fully alert.

That kind of build-up didn’t happen overnight. The car, his precious car, must have been parked here since Tuesday.

And now the shock.

Dante had never left the theater.

Dante was still there!

Preview: Gods and Goddesses — isn’t that what they call movie stars?