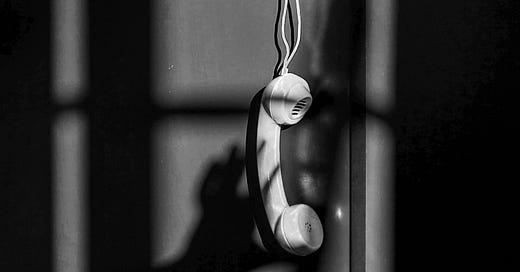

When I think of Noir I think of night and rain.

Seedy downtown streets, darkly gleaming with the shine of lamplights reflected in long, wet gutters.

The protagonist is classically a detective, a dropout from the police force, who knows the law of the pavement, that those who are not on the make are on the take.

A hallmark of Noir is that the cops are as corrupt as the criminals, that law and order are con games, as tawdry and cheap as carnival acts, performed with haughty sobriety by rogue judges to rook the rubes — those people with illusions of fair play, the true believers losing themselves in the hallelujahs of tent revivals.

It is 1943 or thereabouts, and the haves are gaming the system against the have-nots, the Depression-weary common man. World War II broods off stage, never mentioned, but permeating every scene with the storm clouds of a world splitting apart.

Against a background of lowering night, our detective is a professional seeker of truth, of just-the-facts, ma’am. For all his wised-up cynicism, he has a code, a set of ethics, grudgingly out of date in this backstabbing world. And as he descends the various levels of urban hell with the nonchalance of a frequent traveler, cutting a rough, masculine swagger in a trench coat and a fedora yanked down on an angle so that one eye is in shadow, he hunts for something pure in these dirty, smoke-filled dives, in the Georgian mansions of the epicurean rich, disguising with their smooth, cultured patter hearts of darkness.

Here too is another hallmark of Noir: our hardboiled detective knows that deep down he’s a sap, an unrequited lover of all the old virtues, and so with rough resignation, he steels his way through the rain-slick streets where the dames shoot pretty silver bullets straight through your heart and the cops are bought and paid for and never on your side.

When I think of Noir I think of “the stuff that dreams are made of.” Sam Spade’s wry autopsy of what the Maltese Falcon was all about: a chase after a jewel-encrusted gold falcon, one with a fantastical history of kings and knights and pirate plunder, that turns out to be a cold black bird made of nothing but solid lead.*

This, of course, is classic Noir.

The genre has evolved since the 1940s. Chinatown and L.A. Confidential, for instance, are neo-Noir interpretations of the same criminalized world but bring color and daylight to the hard downtown streets.

Both films are examples of a species known as “L.A. Noir,” for the action takes place in the city of Los Angeles, (Hollywood is rarely acknowledged), and the con games are municipal ones. Chinatown’s plot turns on the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, while L.A. Confidential centers on a malevolent police chief and the various vice rackets the cops are extorting for bribes.

An absolutely gorgeous mutation of neo-Noir came out just last year in the new remake of Nightmare Alley.

Even the original Nightmare Alley from 1947 — when the war was over and the Noir vision was fading — was quite the oddball. No corrupt cops, but rather a corrupt universe, brought to life as a fly-by-night carnival, full of freaks and fakes and a rather slick, mathematically manipulated mind-reading scam. A world by and for con jobs.

Interestingly, this new Nightmare Alley adds a wonderful hint of the mystical to the mind reading, as if the carnies are indeed touched by something otherworldly but choose to misuse their slight gifts as nothing more than card tricks.

The carnival folk are not unkind, and we are shown they are not unethical, willing to confess the trick if their mark gets too shaken by a faked encounter with the spirit world. The carnies of this traveling show, unlike, say, the corrupt cops of classic Noir, are underdogs, without power, wised up to a world that is rich and hard and has no place for them to settle. Classic Noir has a jaundiced view of humanity, but here we are made to understand these men and women. They are simply too hungry to be anything but frauds.

Another hallmark: Classic Noir does not have happy endings. It has wry, disillusioned, the stuff that dreams are made of endings. “Go home, Jake — it’s Chinatown” kind of endings.

In this, the new Nightmare Alley is truer to the form than the 1947 black-and-white original, which tacked on a wholely unbelievable love-saves-the-day bit of hokum to its last minute, clearly losing its nerve to tell the full story, to complete its implied shape.

The new Nightmare Alley doesn’t flinch. It is harder, sharper, more darkly intuitive. The film stops at the right moment so that the ending has a rounded quality, a stinging point, the way Aesop’s fables do. It is wryly a Noir parable. And unlike the original, this new, reimagined Nightmare Alley, in the mounting shocks of its last half hour, vividly earns the nightmare of the title.

One other thing that sets the film apart:

Chinatown was bathed in Pacific sunsets and was quite beautiful; L.A. Confidential was electric with crisp performances; but what this new Nightmare Alley has that these other films lack is the heavily stylized look — graphic and fabulously unreal — that conjures up the lost aesthetic of classic Noir.

Director Guillermo del Toro does this by invention rather than imitation. Not by ignoring polychromatic hues and turning them into fake monotones to suggest black and white, but by using color in all its psychological power.

Here is del Toro on the Noir aesthetic:

“Noir isn’t about Venetian blinds and a husky voiceover and a dimly-lit street. It’s not about a dame smoking under a spinning fan. Those are clichés. Those are the Coca Cola commercials of Noir.

“What I understand to be Noir is the real grittiness that comes out of American realism — those films that channel the same spirit as George Bellows or Edward Hopper or Thomas Hart Benton.

“It’s the poetry of disillusionment and existentialism.

“The tragedy that emerges between the haves and have-nots. And the have-nots are trying to reach their ambition through violence and, ultimately, worshipping a hollow god, which is money.

“It’s literally the flip side of the American dream.”

Yes.

Film Noir:

Despite its French name, there is an unmistakable American poetry to this cinema of night and rain-wet streets. Of lonely, cynical saps with big stupid hearts that have been bruised and toughened, who still can’t shake their belief in the better thing, that if they follow the evidence, if they stick to what they know and not to what they are told, they can find it: the virtue amid the vice.

“I needed a drink, I needed a lot of life insurance, I needed a vacation, I needed a home in the country. What I had was a coat, a hat and a gun. I put them on and went out of the room.” ― Raymond Chandler, Farewell, My Lovely

Photos: Dangling phone by Roman Ska; Walking Man by Cameron Casey;

Maltese Falcon screencap, Warner Brothers, 1941, via YouTube.

Nightmare Alley trailer, via YouTube.

*Meanwhile, the Maltese Falcon figurine used in the film sold for $4.1 million in 2013 to Las Vegas casino billionaire Steve Wynn. Though still made of lead and encrusted with nothing but black enamel, the prop, solely on the basis of its movie fame, was, in the end, truly the stuff that dreams are made of.

Yours truly,

Evocative, gorgeous-moody descriptions. And an educational re-learning too. (Was certainly worth the wait.)

Wonderful. Greatly enjoyed this read.